Finding My Roots, Part 2

The turbulent 20th century begins, told through the life of one of my ancestors.

This is the story of my great-great-grandfather, Adolph Widder, and with that a small piece of world history. It’s divided into two parts, the first of which was published here. If you haven’t already, I encourage you to read that first.

The Soldier

Part 1 left off with Adolph, a fresh graduate celebrating his new medical degree, in Budapest, a city celebrating the birth of its new millennium. Adolph had now spent half a decade in the capital. Living in the inner VI district, with his prestigious education, he had integrated into upper-middle-class Budapest society. He was now far from the rural Jews with whom he had grown up.

This capital society however had its own expectations. The emancipation of the Austro-Hungarian Jews in 1867 had been accompanied by another reform. Those leaders who were concerned with integrating the empire? With this goal in mind, and to close the gap between Austria-Hungary and the other great powers, they implemented mandatory conscription in the late 19th century. With his language and medical skills, Adolph would have been certain to be called, and society regardless would have expected him to serve.

Adolph went off to the army to serve the “King and Kaiser” for three years. First, he went to Timisoara, in present-day Romania, for training. Afterwards, he joined up with the 17th regiment, station at Klagenfurt in Austria. His service records list him as highly regarded, “[to] be trusted with leading a large hospital” with “lively spirit, good behavior, open character, [and] friendly,” as well as a “good horseman,” no doubt a result of his years in the village.

Both Timisoara and Klagenfurt were were multicultural hubs, full respectively of Romanians, Hungarians, Jews, Schwabian Germans, and Serbs, and Austrian Germans and Slovenes. By the end of his service, Adolph had now lived in nearly every constituent part of the empire. While the Austro-Hungarians had a few military excursions in China and in the Balkans during this time, none of these touched Adolph or his posts.

The relative peace may have betrayed the coming troubles. Alliances kept the great powers in check, but tensions were brewing under the surface. Furthermore, the nature of war was changing; Adolph’s 1897 training class would have been one of the very last to go through the centuries-old fortress at Timisoara before it was demolished, obsolete in the face of newer, bigger guns.

But for the moment, Adolph emerged from the army into a time of prosperity, with options for the future. He had desirable skills, strong connections and experience, and maybe a touch of a penchant for adventure, a yearning for the mountains of his boyhood and the fresh air of the countryside.

The Doctor

All the way at the edge of the empire, in modern-day Ukraine but even further than the provincial city where Adolph had grown up, lay the town of Bilke.

Decades after the war, Dr. Moshe Avital Doft-Lipschitz would describe the Bilke of the 1930s in his book about the Jewish community there.

“Bilke was a beautiful little town, set in a valley deep in the mountains. No fewer than six streams and rivers rushed down from the heavily forested hills. The story is told that, centuries ago, a local nobleman's daughter drowned while bathing in the big river, and the grieving father gave her name both to the river and town.

The beauty of the town helped neither Jew or non-Jew to escape the general poverty that prevailed in the region known by the name of Sub-Carpathian Ruthenia…

Bilke had a population of about ten thousand, two thousand of them were Jews. It [was] not a homogeneous populace. Among the ten thousand residents of Bilke and surroundings were Ukrainians, Jews, Ruthenian, Hungarians and Czechs. As a result, the people spoke a multitude of languages. In our home we spoke Yiddish. In Cheder or Yeshiva the rabbi spoke Hebrew with Yiddish translation. In Czech school we spoke Czech and with the non-Jewish populace we spoke Ruthenian, the ancient dialect of the peasants.

The Jews of Bilke then numbered over two hundred families. Since they were blessed with ten-twelve children to a family, the total Jewish population came to about two thousand. Their simple homes of brick or clay bricks were spread along or near the main road, well mixed among non-Jews.”

From Our Home Town Bilke

Bilke was peripheral and poor. It was so to the point that the town seems to have had trouble finding a doctor to serve the community. That is, until 1903, when Adolph took on a new challenge. He joined the “Relief Service,” perhaps the Austro-Hungarian equivalent of the modern-day American “National Health Service Corps.” A local newspaper from the time notes that the town had finally managed to secure an applicant for the job, and had promptly selected Adolph for the post.

I can imagine Adolph here, likely the town’s only doctor. On a given day he might have been helping a Ukrainian babushka with her aches and pains, treating the sick child of one of the Hungarian administrators sent from Budapest, calming a Jewish farmer hurt by a horse or mule, likely each in a different language. For three years, Adolph lived this life, serving the least-developed part of the empire.

The Family

Maybe Adolph had imagined staying in Bilke, spending the rest of his life there. Maybe not. But I doubt he expected the twist that would come next.

Remember (from Part 1 again) that Adolph’s elder sister had moved to Berlin with their father a decade prior? Just a half-century earlier, transportation and communication infrastructure in this part of the world would have been too slow and unreliable to allow for much contact. But, by the time of their father’s death in 1894, Central Europe had changed. Adolph visited his sister in Berlin several times and also completed additional medical training there. Even from his rural post, it probably now took only a few days to reach Germany, a previously unimaginable level of connectedness.

It was on one of these Bilke-to-Berlin trips that it happened. Adolph met a girl.

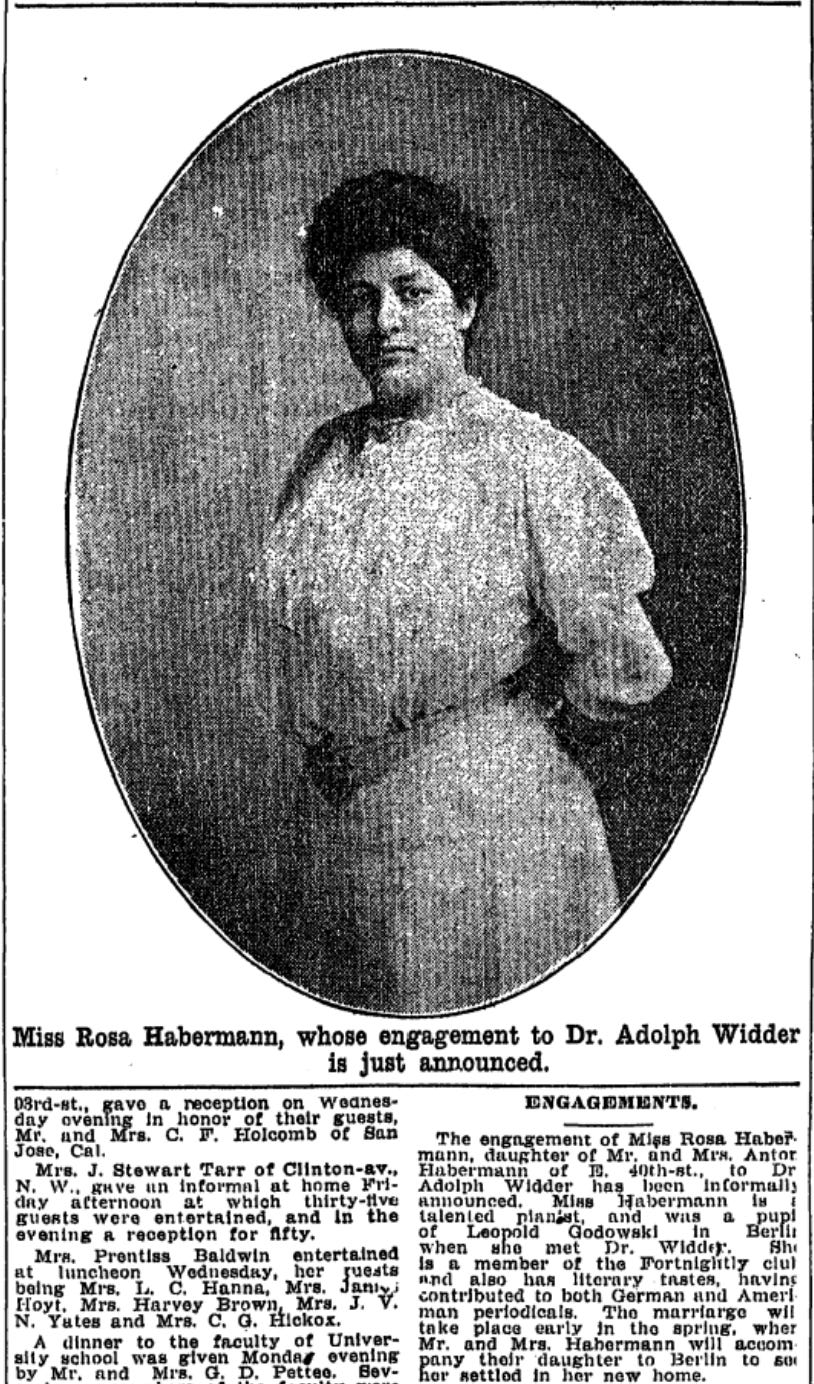

I imagine Rosa Habermann had made a little bit of a splash in the community that year, maybe been the one the Jewish aunties were whispering about and maneuvering to set up with their sons. See, Rosa was the exotic American girl, in Berlin for only a few months or a year. She was also an artist, a concert pianist studying under Leopold Godowsky, then one of the greatest musicians in the world. Perhaps Hermine Widder had assumed her role as older sister and taken it upon herself to be one of those whispering aunties. Maybe she was the best, or maybe Adolph did it on his own.

Regardless, Rosa and Adolph would have quickly discovered some shared experiences. Both had lived something of a nomadic life. It’s unclear where Rosa was born, but her parents were also Hungarian Jews. Her father’s village lay just 100 kilometers from Sobrance, where Adolph was born. The Habermanns had moved to Berlin, then on to Cleveland, Ohio, where she grew up.

After their short romance (can I call it a fling?) Rosa soon returned to Cleveland, and Adolph to Bilke. But they knew already that they were to be married. In September 1906, Rosa’s parents put an article in the Cleveland newspaper proudly announcing their daughter’s engagement to the nice young Jewish doctor in Berlin. Now the Jewish aunties were talking on two continents.

Early in 1907, the pair were married. Within the year, my great-grandfather Milton would be born. Both were, I think, ready to settle down and build their family. They moved to a medium-sized Hungarian city, Nyíregyháza. Adolph opened a new medical practice in the center of town, Rosa played local concerts, and Milton went to school. They took advantage of the peace and prosperity of the first decade of the 20th century. If only it could have lasted.

The Refugee

On June 28, 1914, Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in one of those Balkan peripheries that had seemed like inconsequential skirmishes during Adolph’s time in the army. Within months, Europe was embroiled in what would come to be known as the Great War.

From his quiet life as a doctor in Nyíregyháza, Adolph was pulled into the war effort. Unsurprisingly given his military experience, by the end of the war he had advanced to a rank equivalent to a colonel.

But it would be an understatement to say the war went badly for the unprepared Austro-Hungarian Empire. By 1918, food shortages and inflation were wrecking families at home while military and civilian losses due to the fighting totaled in the millions, more than 3% of the total population. As their military defeat solidified, the empire split up. Hungary voted to separate from Austria, and the various ethnic groups quickly declared their own independence.

This must have felt cataclysmic for Adolph and his family. The army he had fought with was destroyed. But more than that, Sobrance, Uzhhorod, Timisoara, Klagenfurt, and Bilke, nearly all the important places he had lived, were no longer part of his country. Borders, contested and militarized borders with ongoing fighting, now separated Adolph from many of those he knew and loved.

For a very brief year following the end of the war, a Hungarian Jewish communist by the name of Béla Kun led the country. But by 1920, Kun had been exiled and replaced by a right-wing Hungarian government. In the following months, Jews, particularly intellectual and communist-leaning Jews were attacked. Thousands were beaten or murdered. Hungary acquired the distinction of first nation to pass anti-Semitic legislation in the interwar period, restricting Jewish representation at universities with the so-called numerus clausus. The golden age for Hungarian Jews was over.

In 1920 many Jews of the educated upper-class fled, including Adolph, Rosa, and Milton, betrayed by their country. They went mostly to Germany. It was much safer there. So they thought.

The family stayed with Hermine, Adolph’s sister in Berlin, for some months. But eventually, thankfully, they made a fateful choice. Maybe Rosa’s parents insisted they wanted her back home after the decade and a half in Europe. Maybe Adolph had some foresight, some inkling of what was to come. I don’t know. But on October 8, 1920, they boarded a ship bound for New York, aided by Rosa’s American passport, leaving Adolph’s entire life in Hungary behind. They would never return.

In the years that followed, Adolph opened his own medical practice in Cleveland on Buckeye Road where the largest Hungarian community in the United States had coalesced. Rosa continued to perform piano and to support arts organizations in the community. Milton grew up to become a newspaper reporter and local community leader, later named Hungarian of the Year. Throughout this time, the news from family members left in Hungary and Germany would have become progressively more and more worrying. Eventually, it stopped. Rosa searched after the war, but found nobody.

Mercifully, Adolph had passed away in 1940. He didn’t have to live to wonder where his siblings, nieces, and nephews went after they disappeared into Auschwitz. Mercifully too, Hermine passed away in 1941, having survived Kristallnacht but avoided the imminent deportations of Berlin’s Jews to the camps by just a few months.

Conclusion

One of the problems with writing about the Holocaust is that it has a tendency to overshadow, to take over. Writing about a European Jewish family of that time, one must inevitably come to the Holocaust. And one should. In a way, much of my family story was predetermined by the tragedy, equally insomuch as it determines who we became as it determined who else isn’t here to become anything. But here the Holocaust can occupy a story which doesn’t belong to it. Adolph’s story cannot end without it, but to reduce it to that would miss so much. That thread weaves in and out, but I hope I’ve depicted something of the rest of the life and world inhabited by him and many others.

If you found these two posts interesting or thought-provoking, or if you learned something, then I’ve achieved my goal. But truthfully, you probably weren’t the target audience. This one is for the still-living family members, my grandfather, mother, father, and sister, who inspired this piece and everything that went into it with their stories, their memories, their own research, and their questions. Thank you all.

I was on the edge of my seat wondering what happened to Hermine. It was a sort of relief that she and her brother passed before the worst happened. After reading these posts I feel extra grateful that I was able to meet you and work with and become friends with you. C.S. Lewis says that we don't choose our friends, but instead, "friendship is not a reward for our discriminating and good taste in finding one another out. It is the instrument by which God reveals to each of us the beauties of others.” Thanks for sharing these stories, Larkin!