Finding My Roots, Part 1

The end of the 19th century, told through the life of one of my ancestors.

In the hit show Finding Your Roots, now airing its 11th season on PBS, chosen celebrities get a chance to learn about their own family history. The host presents and guides them through a book of research compiled by professional genealogists, highlighting stories of loss, perseverance, and intrigue. Those stories are obviously relevant to the celebrity subjects, but even for a general audience, the lives of these long-dead obscure ancestors of random famous people become somehow captivating. Humanity shines through in its worst, in its best, and in its most human.

If you’ll oblige me, this week I’m going to lay out my own personal version of Finding Your Roots. Specifically, I’m going to trace the life of my great-great-grandfather, Adolph Widder. Now, I’m not famous, and neither was Adolph. But before you click away in sheer boredom, give me a chance. Adolph’s story is of course inherently important to me and to my family, but it’s more than that. His life was uniquely his own, but also represents a story of our world, of the dawn of the modern age and all that promised, of new horizons and new hopes, then of calamity beating those hopes into pessimism, and finally of rebirth and an uncertain new world. All that in the story of one short life.

Note: I use the English spelling of the name Adolph throughout this piece for consistency, though many of the primary sources use the German spelling Adolf.

Adolph’s World

I’m on a train from Budapest to Kosice, the largest city in eastern Slovakia. Throughout Adolph’s story, I’ll weave in an account of my own trip to the important sites of his life. First though, I have to get there. And as I stare out the train window at twilight falling over the Hungarian countryside, it’s a good time to lay out some context.

I think the most logical place to start the story is 1867, just seven years before Adolph would be born. My train stops for half an hour at the Hungarian-Slovak border. Back in 1867 though, all of this was Hungary. Actually, it wasn’t just all Hungary, but also part of the brand-new Austro-Hungarian Empire, the so-called Dual Monarchy, result of a compromise that joined the Kingdom of Hungary and the Austrian Habsburg Empire. That compromise granted both Hungary and Austria internal autonomy, along with control over the other smaller ethnic groups within the empire: Croats, Slovaks, Czechs, Serbs, Slovenes, and others.

This new Austria-Hungary was to be a fully modern state, a multiethnic one in which the rights of all were guaranteed by law. But of course, in practice things weren’t quite so simple. Tensions brewed between the interests of the dozen-odd linguistic groups. Leaders in Budapest and Vienna looked to unify and integrate, encouraging the use of German and Hungarian over minority languages. Jews were traditional targets of persecution, but were spread across the empire and usually spoke Yiddish or German, along with Hungarian or the other local language of the area. Having recognized the utility of such trans-imperial subjects, those leaders followed up the 1867 compromise with laws to emancipate the Jews, to grant them equal rights as citizens, the ability to travel throughout the region, and to access secular universities and other services.

I arrive in Kosice as night falls. The dominant language here is now Slovak, but the occasional menu or sign in Hungarian betrays the past. When Adolph came into the world, this was a multilingual and multireligious place, a bustling regional center of Europe’s newest modern state, and a place of optimism for Jews and Christians alike.

The Village

Following a day sightseeing in Kosice, I get up early to make the trip to where Adolph was born. I’ve had good luck finding Hungarian speakers so far, but that will now change as I head east into the Slovak countryside. My bus moves along the southern edge of the Carpathian mountains, through ever smaller towns. Eventually, I arrive in Sobrance, the last real town before the present Ukrainian border.

Here, on April 3, 1874, Adolph was born to a rural Jewish family, youngest of at least five children. I don’t know much about the life of his father, Emanuel. After all, until emancipation the majority of Jews did not even have official last names. However, like most people of the time including Jews, Emanuel seems to have been a farmer. In 1888, a notice for an auction of his property in the local newspaper lists “1 iron-axled cart, 5 hay carts, 200 bushels of thatch straw, 1 cow, 2 chestnut-gelding horses, 1 two-year foal, and 2 mares.” Adolph would have spent his early years surrounded by his siblings and these animals on a farm in a small, quiet village overlooked by the mountains.

Correction: Someone with better Hungarian pointed out that I slightly misunderstood this auction notice. Emanuel had actually loaned money to another man, Mendel Grünberger, whose property was auctioned to pay off the debt. Instead of a small farmer as I had imagined when this was written, it seems Emanuel may have been one of the bigger landowners in the village.

Not much from that time is left in Sobrance. I find the old Jewish cemetery, now overgrown with thorns the size of my thumb and spend several hours cleaning it as best I can, incurring several wounds in the process. Most of the headstones are written entirely in Hebrew, and most are also worn down by the years. Only a few of the newest are written in Hungarian. I can’t find anyone named Widder, though there must be some of my relatives buried here. The closest I get is a woman named Lotti Roth, just a year or two younger than Adolph and surely an acquaintance, maybe even a friend. She was buried here in 1942 at the age of 66, possibly the last Jew to die in Sobrance before the final deportations to Auschwitz.

The City

Adolph did not stay in Sobrance, and to find where he went next I need to cross another border. My next bus takes me into Ukraine, to the city of Uzhhorod, which was also once part of the Kingdom of Hungary and also once a regional center. Here, the old Megyeház (County Administrative Center) still stands. It’s where my encounter with the security guards from last week’s post took place.

On Megyeház Square, just across from the old building, sits house number 14. This is where Adolph probably spent his formative teenage years. I can’t be sure of that, but years later newspaper advertisements list the house as “for sale” with instructions to contact either Adolph or his brother Jenő. Regardless, Adolph definitely attended school here in Uzhhorod. His 1888 report card from the Catholic Secondary School lists “excellent” results in Religion, Hungarian, History, Math, Gymnastics, and Behavior; “good” in German, Greek, and Natural Science; “acceptable” in Latin.

I can’t tell if the house at Megyeház Square number 14 is the original, or if it’s been demolished and rebuilt. Nobody from my family lives there now anyways. But the old synagogue in Uzhhorod is still there, now serving as the home of the local symphony orchestra. It stands next to the river. Parents push strollers alongside, making it feel almost like the current war doesn’t exist. Uzhhorod today is a nice city, but still a bit sleepy, removed from the wider events in the region.

I imagine that Adolph walked along this river too, looked out from the synagogue after services. Maybe he liked it here. But ultimately, I imagine that he and I feel a similar sense of wanderlust, of something more. It would have been 1892 or 1893 when he graduated high school, and Austria-Hungary along with the world was industrializing, urbanizing, globalizing. The world had changed since Adolph’s father was born in a village, without citizenship, without even a last name. As the Widder children came into adulthood, they took these new opportunities and moved out across central Europe. Adolph’s elder brother Jenő became a pharmacist and moved to Debrecen in Hungary. His older sister, Hermine, married and moved to Berlin accompanied by their father. For Adolph, the youngest, it was time to strike out on his own path.

The Capital

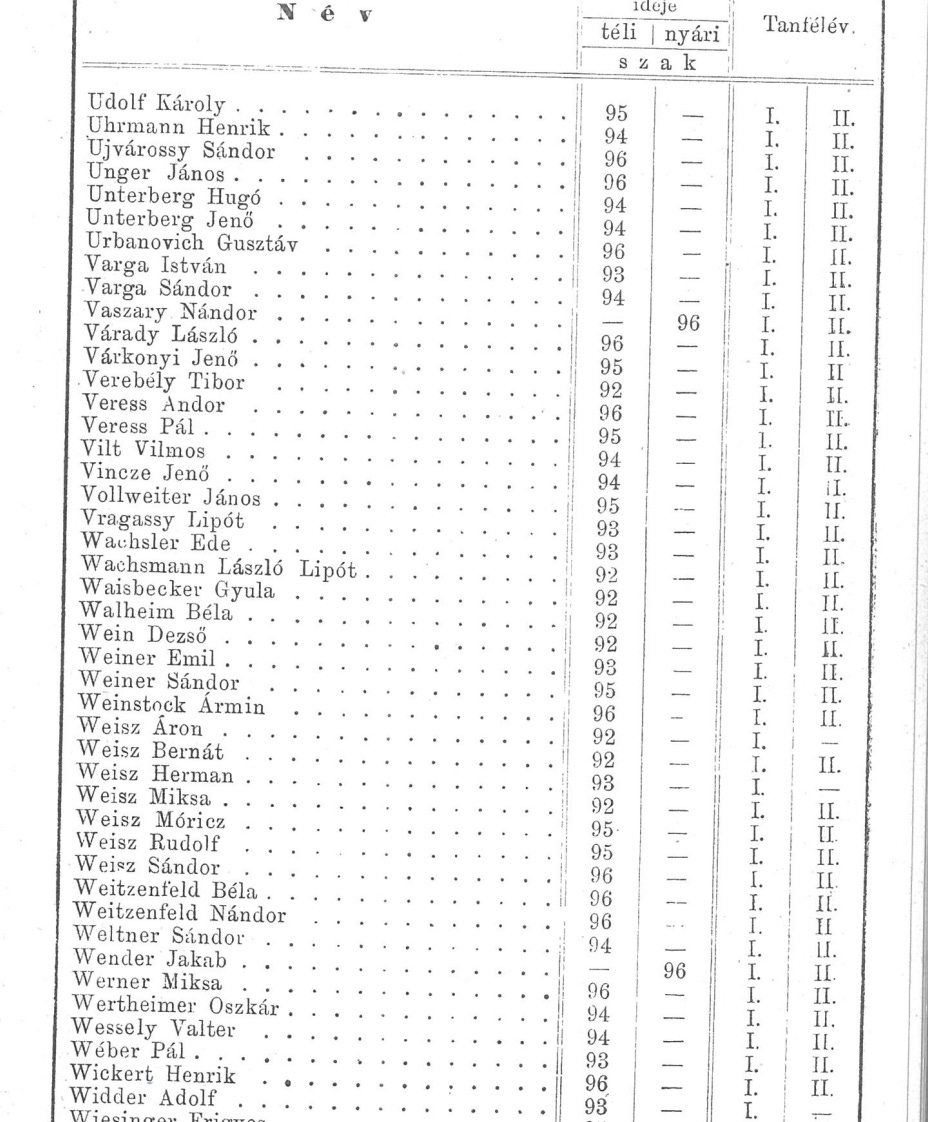

Adolph’s path soon took him from the outer edges of Hungary and the Carpathian Basin to its very heart. In 1893, he enrolled in the medical school at the Catholic university in Budapest, and as records show, graduated four years later.

And what a time it was to be in Budapest, official capital of the Kingdom of Hungary, but arguably cultural capital of the world. 1896 was the year of the millennium, 1,000 years since the almost mythical arrival of the Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin, and the city intended to celebrate.

“From Buda to Pest the King and Queen rode in a crystal-paned baroque coach from Maria Theresa’s time. The holy object of St. Stephen’s crown was brought to the still unfinished, monumental Parliament building.

On the great open field to the west of Castle Hill oxen were broiled on giant spits for the populace. On the eastern edge of Pest a grand world’s fair had been built in the newly laid-out City Park, with many impressive buildings, including a reconstruction of an entire late-medieval Transylvanian castle on the shores of the lake in the park. There were captive balloons, panoramas, a real military balloon ascending, the first movie newsreel made by a Hungarian, the brilliant blaze of electric illuminations, endless music. Budapest had nearly 6 million visitors that year, most of them from the Hungarian provinces.”

- Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City & its Culture, by John Lukacs, pp. 72

A Budapest address directory from 1898 records where Adolph lived, an apartment building in the VI. district of central Budapest, just one street away from the grand Andrássy Boulevard. There, the world’s second underground metro line opened in 1896, just in time to shuttle inhabitants and visitors to the exhibition in City Park. From the door to Adolph’s building, you can see the side wall of the magnificent Hungarian Opera House, then just a decade old, where the greatest conductors and composers of Europe performed and met. New York Cafe, “the most beautiful cafe in the world” opened in 1894, and Budapest was booming; all across the city the ornate apartment buildings which still make the center of the city famous were springing up.

Here too, Jews were finding unprecedented opportunities. The so-called “Martians,” a group of five of the world’s greatest scientists were born around this decade to Hungarian-Jewish families in Budapest. An exploding Jewish middle-class packed the largest synagogue in the world. And not only in what is now called the Jewish Quarter, but across Budapest the intellectual and cultural currents of global Judaism were rooted in this city.

At 24 years old, just about my age, Adolph had just graduated as a young doctor into the liveliest and most dynamic city in Europe. The future held so much promise, not just for him, but for his country. From the village farm in the shadows of the mountains, Adolph had arrived at the center of it all. He must have felt on top of the world.

Next week: Follow along in Part 2 as I continue Adolph’s story through the turbulent decades of the early 20th century, the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the catastrophe that followed.

FINALLY catching up and wow, this was so fun to read. Incredible investigating. I'm excited to read more.

Fantastic job Lark!! I guess excellent gymnastics runs in the family🤸♀️🤸♀️